If you’re new here – welcome! If you’ve been with us here in the Pondering Careers community for a while, then welcome back – this week we have another topic that’s pretty close to my heart – Early Entry programs.

Waaaaay back in 2019 we published the first version of our Early Entry Guide, and back then, it was a pretty new concept. In the years since, and probably in part due to good old Covid, Early Entry has exploded in Australia and become somewhat contentious.

If you’re not from Australia, and/or you don’t know about our Early Entry system (and I use the word ‘system’ loosely) here’s a quick overview:

In addition to, and separate from, the traditional ATAR application process (which you can read about here – thanks University of Sydney) some universities invite school leavers to apply via an alternative Early Entry model, which assesses applications and makes offers before the traditional process is complete.

Students apply using their senior grades, a letter of recommendation from their Principal, their community involvement, extra-curricular activities, or with personal statements (which are sometimes requested in video-format).

Back in 2019 when we published the first version of the Early Entry Guide there were just 17 universities who made some sort of early offer, and they tended to focus on high achievers. These included programs such as La Trobe University‘s Aspire Program, which turned ten this month:

In 2024, there are 33 universities who will offer an Early Entry program, which means that over three quarters of universities are participating now.

In other words – it’s become a big deal, and last year tens of thousands of early offers were made to students, so it’s worth taking a moment to talk about the implications, both positive and negative, of such a system.

Hence, this week I’ll be sharing a couple of my own thoughts, as well as some insights from others in the field. I’m also working with a couple of other incredible Career Advisors to collect some more data around Early Entry, including Claire Pech, so I’ll talk about that as well, because I think it would be great to build a better picture of what’s actually happening.

First up – please ask your Graduates to complete the survey

Before I go any further – if you are from Australia can you please share this link with your past Year 12 students – studyworkgrow.com/education/early-entry-survey/

The survey takes a couple of minutes to complete, and we want to hear from students who received an Early Entry offer.

Thanks!

The current state of Early Entry

Last year felt a little bit like the wild west, as universities made offers from as early as March, and to be honest we all struggled to keep up. I think the first requests from schools for our Early Entry Guide in 2023 came through before the end of Week 1 of the school year, which is just nuts.

This year, things seem a lot more stable.

Following the release of the Universities Accord Final Report a month ago, the education ministers agreed that offers should not be released before September 2024.

So far, we’ve seen the universities comply with this requirement, and all of the universities who have already released their dates have said they won’t be releasing any offers before September.

Some universities always held their offers until later in the year, and it seems that most of these universities will keep their original offer date.

From our end, this doesn’t seem to have overly impacted on the number of students who are thinking about Early Entry, and we’re still getting the same number of phone calls and enquiries from worried students (and their parents), but I’m hopeful that this change will at least give people a bit of certainty.

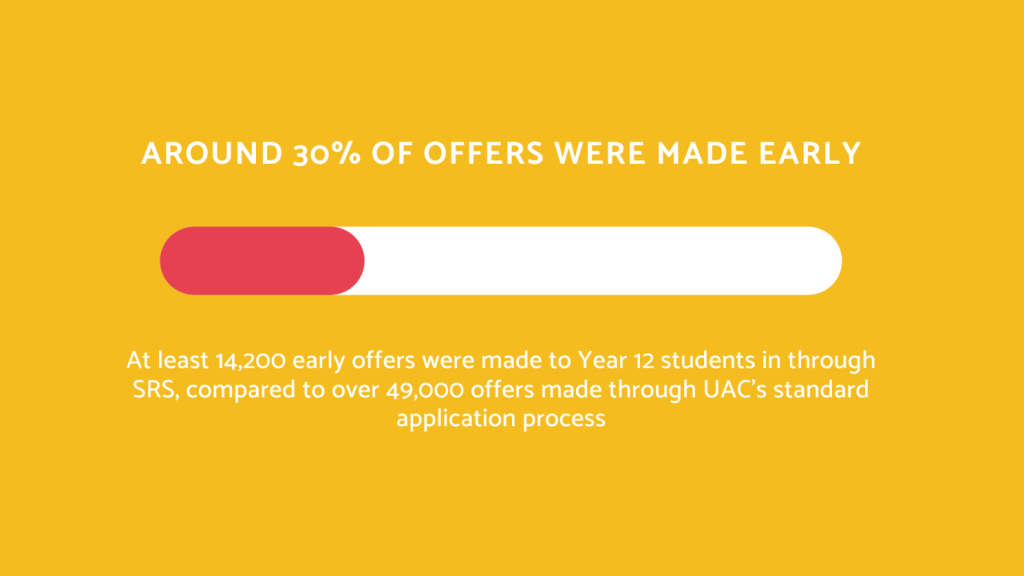

We also see Early Offers making up a significant proportion of the total offer pool:

Each university manages their own early offers, and many students receive more than one offer, which makes it difficult to calculate the real percentage of students who use an early offer to get into university, but there is evidence that a good proportion of students receive an early offer.

It will be interesting to see if the later release date, and the negative press Early Entry has recently received, has any impact on the number of offers which are made in 2024.

Speaking of the negative perceptions of Early Entry, not everyone is pleased with the idea.

In the Universities Accord, they agree that the process is contentious, and that there is little organisation or transparency, and next-to-no available data on early offers.

They note that early offers can reduce stress levels, which is an important consideration in senior schooling, but they also raise concerns that students may ‘disengage’ in their final weeks if they have an early offer.

Dr Sally Patfield from the University of Newcastle recently authored a report into their own experiences with early entry, and you can read it here.

In this study, the team interviewed recipients of Early Entry offers from underrepresented background who had successfully gone on to study at the University of Newcastle.

They found that Early Entry offered significant mental health benefits for students, and that contrary to expectations, rather than ‘slacking off’, students actually felt that they didn’t just work as hard as they would have without the offer, but potentially performed better.

This makes sense – freed of a significant chunk of their stress, they had more brain-space to focus on their study without being overwhelmed by it. Some of the students also reported that the early offer gave them a confidence boost which lifted their self-efficacy and gave them faith in themselves.

This correlates with much of the literature on the impact of positive reinforcement on test results, and I think it’s worth considering when looking at the impacts (if any) on eventual ATARs.

Of course, the concern around slacking off does not come from either the students or the universities, rather, it comes from schools, who traditionally use the ATAR as a yardstick against which they can measure their performance.

As was comprehensively covered in Dr Patfield’s report, the ATAR is not a perfect measure, and it is not held in wide regard by most students.

I don’t want to enter into an argument about the usefulness of the ATAR, but I would say a couple of things. First, the Crunching the Number Discussion Paper from Sarah Pilcher and Kate Torii is an excellent overview of the intended and unintended (but actual) uses of the ATAR, and it was written back in 2018, well before Early Entry became a big ‘thing’. As they said back then:

“While this ranking of school leavers remains important, it is also true that in 2017, 60 per cent of undergraduate university offers were made on a basis other than ATAR. This would surprise many young people, as it seems at odds with the message reinforced by many schools, families and the media – that the ATAR is everything.”

In other words, the ATAR was becoming less relevant well before Early Entry was a factor. And it didn’t start there; this paper from George Cooney back in 2001 (23 years ago) posed the question, ‘Is the Tertiary Entrance Rank an endangered species?’ (the Tertiary Entrance Rank or ‘TER’ was the predecessor of the UAI, which eventually became the ATAR, all of which basically do the same thing).

George pondered the implications of university admissions processes on what we teach in the senior years, and how we teach it, but he went back even further, and quoted a professor from the late 1800s who complained that university admissions dictated what was taught in high school.

In other words, criticism of the ATAR isn’t new.

What is new, is the potential threat to the ATAR – Early Entry – and in this context it’s not overly surprising that there has been some push back from the establishment against the establishment’s old, easily-comparable friend.

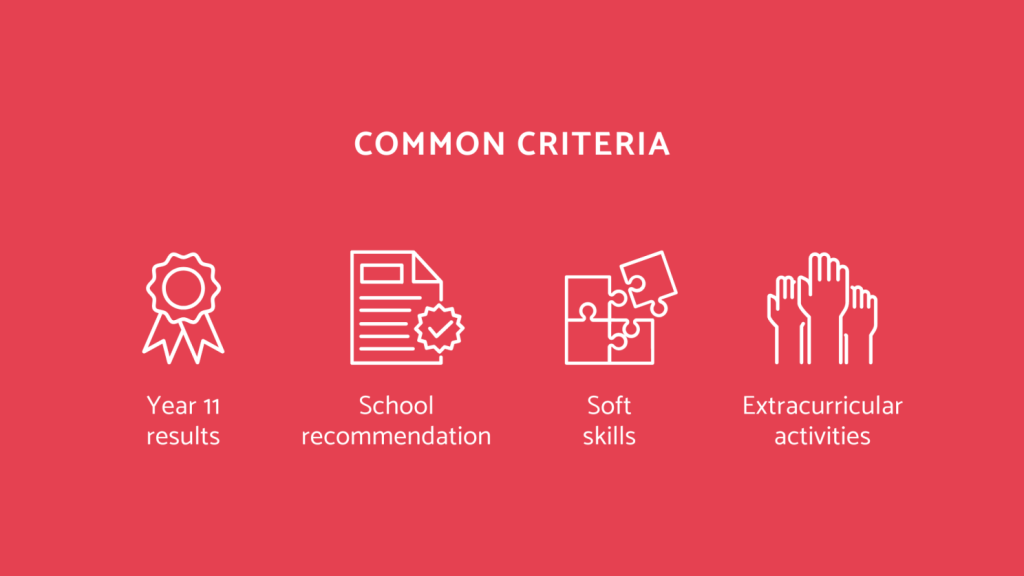

Next question – if Early Entry programs don’t use the ATAR, what do they use instead?

They use a wide range of measures, which tend to reflect the priorities of the individual universities (which is probably the first indication that, when given the chance, universities will choose to admit students based on their own priorities).

So, universities that focus on widening participation will ask for measures which go beyond academics – community participation, volunteering and sporting activity, work experience and personal statements. Universities that are seeking a diversely talented cohort might offer Early Entry based on portfolio, audition, or interview, and it seems that many universities are happy to trust the recommendation of the school Principal.

To be honest, it seems that when given the chance the universities will set up systems that allow them to screen and recruit the type of students they would prefer, which reminds me of the system in the US.

And, while this may not suit some students who have prioritised their ATAR over everything else in their lives, this actually ends up with well-rounded students who focus on a range of skills, not just academics.

Medical programs are another example of where this shift has taken place – 10 years ago we would list medical programs and in almost every case they admitted solely on the basis of ATAR. Today, the ATAR is just a hurdle, and medical students need to be able to juggle study with work, extra-curricular activities, and community involvement if they want to be competitive.

Which makes sense, because no one wants a system that produces academically excellent robots who are unable to function without a parent to manage every other aspect of their lives.

Does this make the programs less equitable?

This was a claim made by the Universities Accord:

“…there is a risk that early offers can favour students who have existing personal or socio-economic advantages such as strong school performances, principal and parent advocacy, school culture and career guidance, and community and extracurricular claims.”

Now, I admit that, on the surface, this is a risk.

We can see what could happen down the track when we look at systems like the one in the US, which has an entire industry set up to ensure the kids who can afford it get into their college of choice.

Students who cannot afford experts to help them write their admissions essays or prepare for interviews are obviously going to be at a disadvantage.

In response, I would say two things:

Things are already inequitable

Students who can afford tutors, who don’t need to work 16+ hours a week, and who can afford to participate in extra-curricular activities (because those things are expensive) are going to be at an advantage. They are already probably at schools which provide more support, and they’re surrounded by peers who also have these advantages.

Only someone with zero experience of the ATAR and senior schooling in Australia would suggest that the ATAR system is set up to level the playing field. The brightest child in Australia will be scaled down if they live in a rural community, that’s just how the system is set up.

The other thing to consider is the economic privilege of being able to wait until you receive an offer in January before working out where (or if) you’ll be going to university.

This is a huge privilege, and even more so when compared to low SES regional students, who will inevitably need to relocate to attend university. Asking regional students without a lot of funds to wait until January to know where they will be studying means they have to wait until January to arrange accommodation, and most of it is expensive and already booked out by January.

It also means they may turn down secure employment until after they receive their offer, or, alternatively, take the secure employment offer rather than risk it and wait for an offer for uni that might never come.

Early Entry can actually improve equity

By its very nature, Early Entry widens participation.

People who wouldn’t normally have applied or considered themselves a good chance at getting an offer give Early Entry a shot because of the way it is set up. They don’t need a high ATAR, and they can be valued for their other abilities and experiences, which gives them an alternative pathway to uni.

Many of the programs are actually set up to encourage applications from underrepresented groups, including First Nations people and those from regional and rural backgrounds.

Some of the programs are actually designed so students with an offer don’t even need to finish school, and these programs are those targeted at underrepresented groups.

Dr Patfield’s work also supports this; the students she interviewed talked about how without Early Entry they would not have applied for uni. They were first-in-family, or came from schools with low expectations for university study, but Early Entry gave them a chance.

Receiving an Early Offer before they finished school allowed them to start planning out where they would live, and they could transfer or seek new employment that would suit that university.

Plus, it gives them a confidence boost – the value of which cannot be understated. Universities make it easy for students to apply, and give them lots of support throughout the process, which is vastly different from the impersonal and remote ATAR process.

Want an example? Here’s Hunter the Hippocampus from the University of Newcastle to help you apply:

The value of an alternative route to university lies in its flexibility, and my hope is that the proposed regulation of the system doesn’t impinge on what’s working well.

Perhaps we just need some new KPIs?

I’ve already seen a number of schools proudly declaring the number of early offers their students received, and it’s a great marketing metric for schools to be able to share, so, potentially we just need to shift the conversation sideways a little and start measuring some new metrics.

We can let go of the days where the number of ATARs above a certain mark are all that counts, and start celebrating our early offers, apprenticeships, and even congratulate students who find work straight out of school.

That way, schools would still be able to compare their performance, and students could follow the post-school pathway of their choosing.

What do you think? Do you hate early entry, or have you had good experiences? I’d love to hear either way, so please share your own thoughts, and, as always, thanks for joining me again this week.

You can read previous editions of Pondering Careers here.